Indian Rhinoceros

| Indian Rhinoceros[1] | |

|---|---|

| Indian rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Rhinoceros |

| Species: | R. unicornis |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhinoceros unicornis Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

|

|

| Indian Rhinoceros range | |

The Indian Rhinoceros or the Great One-horned Rhinoceros or the Asian One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) is a large mammal primarily found in north-eastern India and Nepal. It is confined to the tall grasslands and forests in the foothills of the Himalayas. Weighing somewhere between 2260 kg and 3000 kg, it is the fourth largest land animal. Belonging to the Rhinocerotidae family, the Indian rhino is listed as an endangered species. It has a single horn, which measures between 20 cm to 57 cm in length.

The Indian Rhinoceros once ranged throughout the entire stretch of the Indo-Gangetic Plain but excessive hunting reduced their natural habitat drastically. Today, about 3,000 Indian Rhinos live in the wild, 2000 of which are found in India's Assam alone.[3]

The Indian Rhinoceros can run at speeds of up to 55 km/h (34 mph) for short periods of time and is also an excellent swimmer. It has excellent senses of hearing and smell but relatively poor eyesight.

Contents |

Taxonomy

The Indian Rhinoceros was the first rhinoceros known to Europeans.[Citation?] Rhinoceros from the Greek, "rhino" meaning nose and "ceros" meaning horn. The Indian Rhinoceros is monotypic, meaning there are no distinct subspecies. Rhinoceros unicornis was the type species for the rhinoceros family, first classified by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758.[4]

Evolution

Ancestral rhinoceroses first diverged from other Perissodactyls in the Early Eocene. Mitochondrial DNA comparison suggests that the ancestors of modern rhinos split from the ancestors of Equidae around 50 million years ago.[5] The extant family, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia, and the ancestors of the extant rhino species dispersed from Asia beginning in the Miocene.[6]

Fossils of Rhinoceros unicornis appear in the Middle Pleistocene. In the Pleistocene, the Rhinoceros genus ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South Asia, with specimens located on Sri Lanka. Into the Holocene, some rhinoceros lived as far west as Gujarat and Pakistan until as recently as 3,200 years ago.[4]

The Indian and Javan Rhinoceros, the only members of the genus Rhinoceros, first appear in the fossil record in Asia around 1.6 million–3.3 million years ago. Molecular estimates, however, suggest the species may have diverged much earlier, around 11.7 million years ago.[5][7] Although belonging to the type genus, the Indian and Javan Rhinoceros are not believed to be closely related to other rhino species. Different studies have hypothesized that they may be closely related to the extinct Gaindetherium or Punjabitherium. A detailed cladistic analysis of the Rhinocerotidae placed Rhinoceros and the extinct Punjabitherium in a clade with Dicerorhinus, the Sumatran Rhino. Other studies have suggested the Sumatran Rhinoceros is more closely related to the two African species.[8] The Sumatran Rhino may have diverged from the other Asian rhinos as far back as 15 million years ago.[6][9]

Description

In size it is equal to that of the white rhino in Africa; together they are the largest of all rhino species. Fully grown males are larger than females in the wild, weighing from 2,200 to 3,000 kg (4,900 to 6,600 lb). Female Indian rhinos weigh about 1,600 kg. The Indian Rhino is from 1.7 to 2 m (5 ft 7 in to 6 ft 7 in) tall and can be up to 4 m (13 ft) long. The record-sized specimen of this rhino was approximately 3,500 kg.

The Indian rhinoceros has a single horn; this is present in both males and females, but not on newborn young. The horn, like human fingernails, is pure keratin and starts to show after about 6 years. In most adults the horn reaches a length of about 25 centimeters,[10] but have been recorded up to 57.2 centimeters in length. The nasal horn curves backwards from the nose. Its horn is naturally black. In captive animals, the horn is frequently worn down to a thick knob.[4]

This prehistoric-looking rhinoceros has thick, silver-brown skin which becomes pinkish near the large skin folds that cover its body. Males develop thick neck-folds. Its upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps. It has very little body hair, aside from eyelashes, ear-fringes and tail-brush.[4]

In captivity, four are known to have lived over 40 years, the oldest living to be 47.[4]

Behavior

These rhinos live in tall grasslands and riverine forests but due to habitat loss they have been forced into more cultivated land. They are mostly solitary creatures, with the exception of mothers and calves and breeding pairs, although they sometimes congregate at bathing areas. They have home ranges, the home ranges of males being usually 2-8 square kilometers in size, and overlapping each other. Dominant males tolerate males passing through their territory except when they are in mating season, when dangerous fights break out. They are active at night and early morning. They spend the middle of the day wallowing in lakes, rivers, ponds, and puddles to cool down. They are extremely good swimmers. Over 10 distinct vocalizations have been recorded.

Indian rhinos have few natural enemies, except for tigers. Tigers sometimes kill unguarded calves, but adult rhinos are less vulnerable due to their size. Humans are the only other animal threat, hunting the rhinoceros primarily for sport or for the use of its horn. Mynahs and egrets both eat invertebrates from the rhino's skin and around its feet. Tabanus flies, a type of horse-fly are known to bite rhinos. The rhinos are also vulnerable to diseases spread by parasites such as leeches, ticks, and nematodes. Anthrax and the blood-disease septicemia are known to occur.[4]

Diet

1_-_Relic38.jpg)

The Indian Rhinoceros is a grazer. Their diet consists almost entirely of grasses, but the rhino is also known to eat leaves, branches of shrubs and trees, fruits and submerged and floating aquatic plants.[4]

Feeding occurs during the morning and evening. The rhino uses its prehensile lip to grasp grass stems, bend the stem down, bite off the top, and then eat the grass. With very tall grasses or saplings, the rhino will often walk over the plant, with its legs on both sides, using the weight of its body to push the end of the plant down to the level of the mouth. Mothers also use this technique to make food edible for their calves. They drink for a minute or two at a time, often imbibing water filled with rhinoceros urine.[4]

Social life

The Indian Rhinoceros forms a variety of social groupings. Adult males are generally solitary, except for mating and fighting. Adult females are largely solitary when they are without calves. Mothers will stay close to their calves for up to four years after their birth, sometimes allowing an older calf to continue to accompany her once a newborn calf arrives. Subadult males and females form consistent groupings as well. Groups of two or three young males will often form on the edge of the home ranges of dominant males, presumably for protection in numbers. Young females are slightly less social than the males. Indian Rhinos also form short-term groupings, particularly at forest wallows during the monsoon season and in grasslands during March and April. Groups of up to 10 rhinos may gather in wallows—typically a dominant male with females and calves, but no subadult males.[11]

The Indian Rhinoceros makes a wide variety of vocalizations. At least ten distinct vocalizations have been identified: snorting, honking, bleating, roaring, squeak-panting, moo-grunting, shrieking, groaning, rumbling and humphing. In addition to noises, the rhino uses olfactory communication. Adult males urinate backwards, as far as 3–4 meters behind them, often in response to being disturbed by observers. Like all rhinos, the Indian Rhinoceros often defecates near other large dung piles. The Indian Rhino has pedal scent glands which are used to mark their presence at these rhino latrines. Males have been observed walking with their heads to the ground as if sniffing, presumably following the scent of females.[11]

In aggregations, Indian Rhinos are often friendly. They will often greet each other by waving or bobbing their heads, mounting flanks, nuzzling noses, or licking. Rhinos will playfully spar, run around, and play with twigs in their mouth. Adult males are the primary instigators in fights. Fights between dominant males are the most common cause of rhino mortality and males are also very aggressive toward females during courtship. Males will chase females over long distances and even attack them face-to-face.[11] Unlike African Rhinos, the Indian Rhino fights with its incisors, rather than its horns.[12]

Reproduction

In zoos, females may breed as young as four, but in the wild females are usually six before breeding begins.[13] The higher age in the wild may reflect that females need to be large enough to avoid being killed by the aggressive males. The Indian Rhinoceros has a very lengthy gestation period of around 15.7 months. The interval between births ranges from 34–51 months.[13] In captivity, males may breed at five years. But in the wild, dominant males do the breeding and rhinos do not attain dominance until they are older and larger. In one five-year field study, only one rhino who achieved mating success was estimated to be younger than 15.[14]

Distribution

The rhino once ranged throughout northern India from Peshawar to Burma. About 5,000 years ago, it inhabited the Indus Valley in Pakistan. As a result of habitat destruction and climatic changes their range has gradually been reduced so that by the 19th century, they only survived in the Terai grasslands of southern Nepal, northern Uttar Pradesh, northern Bihar, northern Bengal, and in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam.[15]

On the former abundance of the species, Thomas C. Jerdon wrote in 1874 in the Mammals of India:

This huge rhinoceros is found in the Terai at the foot of the Himalayas, from Bhotan to Nepal. It is more common in the eastern portion of the Terai than the west, and is most abundant in Assam and the Bhotan Dooars. I have heard from sportsmen of its occurrence as far west as Rohilcund, but it is certainly rare there now, and indeed along the greater part of the Nepal Terai; ... Jelpigoree, a small military station near the Teesta River, was a favourite locality whence to hunt the Rhinoceros and it was from that station Captain Fortescue, of the late 73rd N.I., got his skulls, which were, strange to say, the first that Mr. Blyth had seen of this species, of which there were no specimens in the Museum of the Asiatic Society at the time when he wrote his Memoir on this group.—Jerdon, T. C. 1874 The Mammals of India.

Today, their range has further shrunk to a few pockets in southern Nepal, northern Bengal and the Brahmaputra Valley. In the 1980s, rhinos were frequently seen in the narrow plain area of Royal Manas National Park in Bhutan. In the early 1980s, a rhino translocation scheme was initiated. The first pair of rhinos was reintroduced from the Nepal Terai to Pakistan's Lal Suhanra National Park in Punjab in 1982. In 1984, five rhinos were relocated to Dudhwa National Park -- four from the fields outside the Pabitora Wildlife Sanctuary and one from Goalpara.[15]

Population and threats

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Indian Rhinoceros was hunted relentlessly and persistently. Reports from the middle of the nineteenth century claim that some military officers in Assam individually shot more than 200 rhinos. In the early 1900s, officials became concerned at the rhino's plummeting numbers. By 1908 in Kaziranga, one of the rhino's main ranges, the population had fallen to around 12 individuals. In 1910, all rhino hunting in India became prohibited.[4]

This rhino is a major success of conservation. Only 100 remained in the early 1900s; a century later, their population has increased to about 2500 again, but even so the species is still endangered. The Indian rhino is illegally poached for its horn, which some cultures in East Asia believe has healing and potency powers and therefore is used for Traditional Chinese Medicine and other Oriental medicines. Habitat loss is another threat.

The Indian and Nepalese governments have taken major steps toward Indian Rhinoceros conservation with the help of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The Kaziranga National Park and Manas National Park, Pobitora reserve forest (having the highest Indian rhino density in the world), Orang National Park and Laokhowa reserve forest in Assam have very small populations.

In 2008, more than 400 Indian Rhinos were sighted in Nepal's Chitwan National Park.[16]

| Location | Number of rhinos | Total area |

|---|---|---|

| Kaziranga NP, Assam | 1600 + | 430 km2 |

| Chitwan NP, Nepal | 600 + | 932 km2 |

| Pobitara WLS, Assam | 78 | 16 km2 |

| Jaldapara WLS, West Bengal | 65 | 21 km2 |

| Orang NP, Assam | 46 | 78 km2 |

| Gorumara NP, West Bengal | 32 | 8.88 km2 |

| Manas NP | Doubtful existence | - |

| Laokhowa WLS | None known | - |

| Location | Number of rhinos |

|---|---|

| Dudhwa NP/ TR, India | 21 |

| Bardia NP, Nepal | 85 |

| Sukhla Phanta WLR, Nepal | 16 |

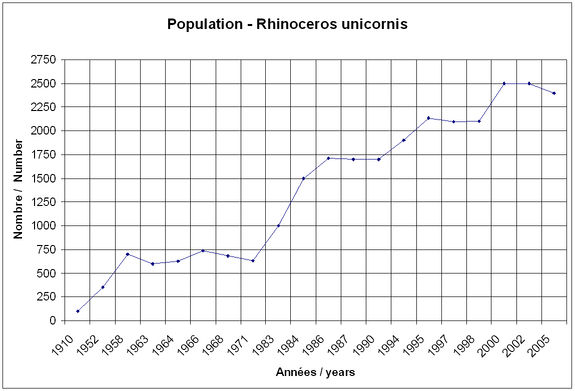

Demographic trends of Rhinoceros unicornis. Sources : here.

|

|

In captivity

The Indian Rhinoceros was initially difficult to breed in captivity. The first recorded captive birth of a rhinoceros was in Kathmandu in 1826, but another successful birth did not occur for nearly 100 years; in 1925 a rhino was born in Kolkata. No rhinoceros was successfully bred in Europe until 1956. On September 14, 1956 Rudra was born in Zoo Basel, Switzerland.

In the second half of the 20th century, zoos became adept at breeding Indian rhinoceros. By 1983, nearly 40 had been born in captivity.[4] As of 2008, 31 Indian rhinos were born at Zoo Basel (history), which means that most animals kept in a zoo are somehow related to the population in Basel, Switzerland.

Cultural depictions

|

|

| Artist | Albrecht Dürer |

|---|---|

| Year | 1515 |

| Type | woodcut |

| Dimensions | 24.8 cm × 31.7 cm (9.8 in × 12.5 in) |

The Indian Rhinoceros was the first rhino widely known outside its range. The first rhinoceros to reach Europe in modern times arrived in Lisbon on May 20, 1515. King Manuel I of Portugal planned to send the rhinoceros to Pope Leo X, but the rhino perished in a shipwreck. Before dying, however, the rhino had been sketched by an unknown artist. A German artist, Albrecht Dürer, saw the sketches and descriptions and created a woodcut of the rhino, known ever after as Dürer's Rhinoceros. Though the drawing had some anatomical inaccuracies (notably the hornlet protruding from the rhino's shoulder), his sketch became the enduring image of a rhinoceros in western culture for centuries.

Assam state of India has one-horned rhino as the official state animal. It is also the organizational logo for Assam Oil Company Ltd.

Footnotes

- ↑ Wilson, Don E.; Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds (2005). Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14100071.

- ↑ Talukdar, B.K., Emslie, R., Bist, S.S., Choudhury, A., Ellis, S., Bonal, B.S., Malakar, M.C., Talukdar, B.N. Barua, M. (2008). Rhinoceros unicornis. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 28 November 2008.

- ↑ Sarma, P.K., Talukdar, B.K., Sarma, K., Barua, M. (2009) Assessment of habitat change and threats to the greater one-horned rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Pabitora Wildlife Sanctuary, Assam, using multi-temporal satellite data. Pachyderm No. 46 July–December 2009: 18-24 pdf download

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Laurie, W.A.; E.m. Lang, and C.P. Groves (1983). "Rhinoceros unicornis". Mammalian Species (American Society of Mammalogists) (211): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504002. http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/Biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/default.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Xu, Xiufeng; Axel Janke, and Ulfur Arnason (1 November 1996). "The Complete Mitochondrial DNA Sequence of the Greater Indian Rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis, and the Phylogenetic Relationship Among Carnivora, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla (+ Cetacea)". Molecular Biology and Evolution 13 (9): 1167–1173. PMID 8896369. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/13/9/1167. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lacombat, Frédéric. The evolution of the rhinoceros. In Fulconis 2005, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Tougard, C.; T. Delefosse, C. Hoenni, and C. Montgelard (2001). "Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 19 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0903. PMID 11286489.

- ↑ Cerdeño, Esperanza (1995). "Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)". Novitates (American Museum of Natural History) (3143). ISSN 0003-0082. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/3566/1/N3143.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ↑ Dinerstein 2003, pp. 10–15

- ↑ Dinerstein 2003, pp. 272

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Dinerstein 2003, pp. 283–286

- ↑ Dinerstein 2003, pp. 134–135

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Dinerstein 2003, pp. 142

- ↑ Dinerstein 2003, pp. 148–149

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Choudhury, A. U. (1985) Distribution of Indian one-horned rhinoceros. Tiger Paper 12(2): 25-30

- ↑ Basu P. (2008) Rare One-Horned Rhino Bouncing Back in Nepal. National Geographic News article online

References

- Dinerstein, Eric (2003). The Return of the Unicorns; The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

- Foose, Thomas J. and van Strien, Nico (1997). Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- Fulconis, R. (ed.) (2005). Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria.

See also

- The Soul of the Rhino (book)

External links

- The Rhino Resource Center

- Indian Rhino on Kaziranga National Park Official website

- Indian Rhino page at International Rhino Foundation website

- Greater Indian Rhinoceros page at TheBigZoo.com

- Indian Rhino page at AnimalInfo.org

- Indian Rhino page at AmericaZoo.com

- Indian Rhinoceros page at nature.ca

- Page Rhinocéros indien à nature.ca

- Indian Rhinoceros page at UltimateUngulate.com

- Population of Indian one-horned rhinoceros in India and Nepal

- Short narrated video about the Indian Rhinoceros

- Images, videos and information on the Indian Rhinoceros

- Asian Rhino Foundation

- Indian Rhino photo gallery

- Indian army to help prevent rhino poaching

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||